Every brain begins with a blueprint—but what happens when that blueprint changes? At the University of South Carolina, developmental neuroscientist Kristy Welshhans investigates how the brain builds its complex wiring during early development and what happens when those connections don’t form as expected.

Her research focuses on conditions like Down syndrome, the most common chromosomal condition in the U.S., which affects about one in every 775 babies. While all individuals with Down syndrome experience some level of cognitive delay, says Welshhans, the biological reasons behind those differences remain an active area of discovery.

Welshhans’s work has the potential to inform future therapies and improve quality of life for individuals with developmental disabilities. But her impact goes beyond the lab bench. As a 2025 Distinguished Undergraduate Research Mentor Award winner, she also helps students get early training in real scientific research.

We spoke with Dr. Welshhans about her research, her approach to mentorship and the opportunities available for undergraduates who are ready to dive into brain science.

For those who may not be familiar—what does undergraduate research actually look like in your lab?

The first semester is all about learning the pieces—techniques, tools and how experiments are set up. Students typically come in three days a week for a few hours to monitor cells, practice culturing and imaging and learn how to analyze and interpret data. By the second semester, they’re usually ready to carry out an experiment on their own. Recently, eight undergraduate students in the lab contributed to two research papers on Down syndrome and earned authorship for their work.

How do you describe your research to someone without a science background?

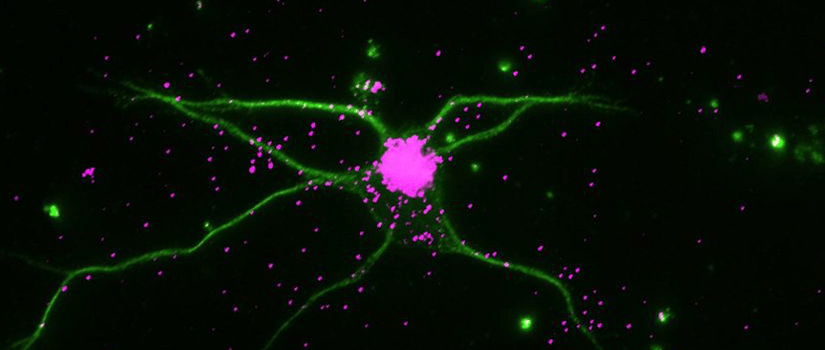

We study how the brain develops before birth, especially during the embryonic stage. Using mouse models and donated human cells, we look at how neurons grow and connect.

One major focus is Down syndrome, which happens when there’s an extra copy of chromosome 21. That extra copy causes too much of certain proteins to be made, which can lead to challenges like heart defects, vision or hearing problems and intellectual disability.

What are some of the big questions your lab is trying to answer, and why do they matter?

We want to understand why the brain connectivity in Down syndrome doesn’t form typically. Billions of neurons and trillions of connections must be made precisely in utero—so why do they form atypically, and what proteins are involved?

While we don’t expect to find a “cure,” we hope this work contributes to developing treatments that improve quality of life. For example, many individuals with Down syndrome develop early-onset Alzheimer’s. If we understand the biology better, we can help pharmaceutical researchers create targeted therapies. It’s about helping people live fuller, more independent lives.

How do you help students, especially those new to research, build confidence and grow as scientists?

We pair every undergraduate with a graduate student mentor. It makes the lab feel less intimidating—grad students are closer in age and can walk them through the technical side, like pipetting or imaging. I guide the intellectual side—why we’re doing the experiment, how to interpret what we find and how to move forward if something goes wrong. The technical side can be frustrating at first. It’s repetitive. It doesn’t always work. But that’s part of the process. Understanding the “why” helps students stay motivated, even when experiments fail.

Can you share a story about a student you mentored who had a breakthrough moment in the lab?

A senior honors student joined the lab, and during her first semester felt frustrated and discouraged at first. I reassured her that what she was experiencing was completely normal and that she was doing just fine. That second semester, she completed her first full experiment and was amazed by the outcome. She stayed on through the summer, working on more advanced experiments. Watching her grow from self-doubt to confidence was such a rewarding transformation.

What do your students go on to do after working in your lab? How does research shape their future paths?

Some head to medical school, others to graduate programs and some are still figuring it out. Whatever their path, I meet them where they are. But the skills they learn—critical thinking, perseverance and presenting research—are valuable in any field. Science fails most of the time. Learning to push through failure, troubleshoot and try again is something students will take with them no matter where they go.

What’s the best way for a curious student to get involved in research as an undergraduate?

Email me! Or talk to graduate students in our lab if you're nervous. We also have a lab website with more info.

If you're interviewing for a research position, be curious and engaged. Read about what we do ahead of time. You don’t need to know everything—but show that you’re interested and open to learning what a day in the lab really looks like.

Research Funding to help you

Looking to get started in research? Connect with opportunities for funding, mentorship and real lab experience—starting as early as your first year.

- Get paid to do research during the semester or summer

- Strengthen your resume with grant writing, lab skills, and presentations

- Present your work at Discover USC or even national conferences

Check out the Office of Undergraduate Research to find the right fit and get started.